By Pycior, Julie Leininger

Moyers, Bill? He is amazing! George Clooney stated, and it makes sense.

Following Clooney’s return from the Broadway stage, where he had recently been playing another journalistic giant, Edward R. Murrow, I brought up this renowned television journalist to the actor and director. In a memorial to Moyers, the Museum of Broadcast Communications stated that he was among the few broadcast journalists who could be considered to be on par with Edward R. Murrow. Moyers greatly expanded the traditions of broadcast journalism, if Murrow was its founder.

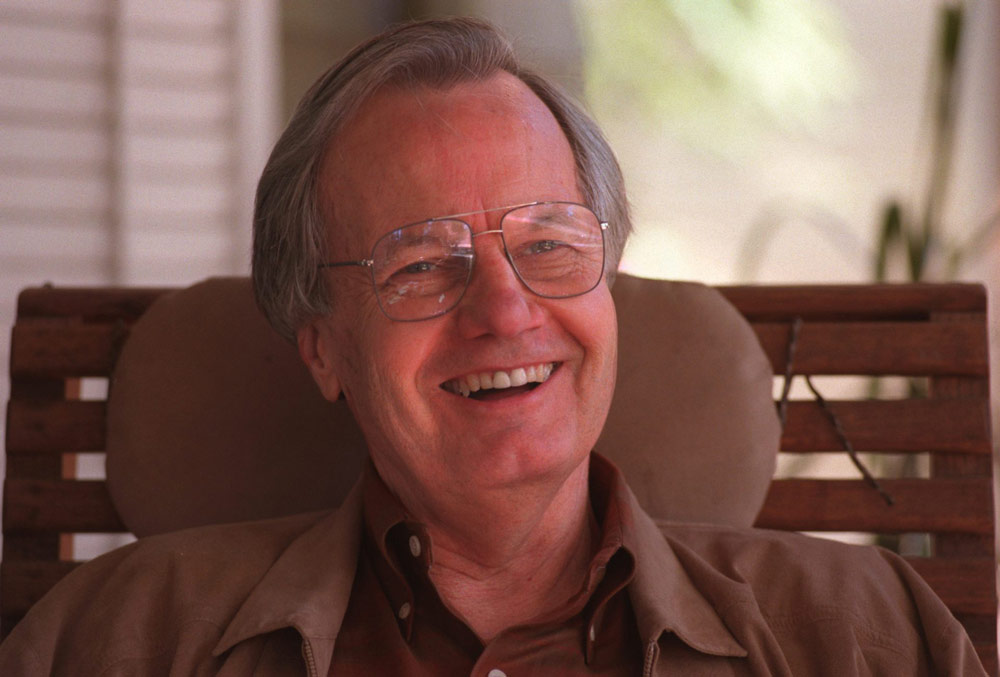

One of the most celebrated broadcast journalists of the 20th century, Moyers passed away on June 26, 2025, at the age of 91. He is well-known for his TV news programs that highlighted the influence of large corporations on politics and for highlighting underappreciated democratic advocates like community organizer Ernesto Corts Jr.

Although Moyers played important positions in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations earlier in life, his journalism is what made him famous.

Making a connection

In person, Moyers was just as grounded as he appeared to be on TV, despite his notoriety. I was a historian at home with a preschooler in 1986, teaching the occasional college course in a bleak job market while he was dominating a television audience of millions. I wrote to Moyers because I knew he would be speaking at the conference on President Lyndon B. Johnson, where I would be presenting a presentation.

He responded, and to my complete surprise, he came to hear my paper about Johnson’s experiences as a young administrator of the Mexican school in Cotulla, Texas, where he supported his pupils while also establishing connections with segregationists. According to Moyers, Cotulla was essential to LBJ’s growth. He suggested me for a grant in 1993, which enabled me to complete LBJ and Mexican Americans: The Paradox of Power.

A few years later, he asked me to lead an investigation into the records pertaining to his tenure in the Johnson administration. He never wrote a memoir about the Johnson years. Rather, the best-selling book Myers on America: A Journalist and His Times was edited by myself.

Moyers’ conviction that what counts is not one’s proximity to power but rather one’s proximity to truth is one of the things that has always impressed me about him.

Amazing Grace

As a journalist, Moyers focused on more than just politics and policy. He also explored the life of the mind and the significance of creativity. He featured scientists, novelists, and other remarkable individuals in many of his most poignant conversations.

He was perhaps one of the top reporters covering religion as well. He was a lifelong spiritual seeker, even though it wasn’t always the primary emphasis of his work or what those familiar with his legacy would think of him by.

It should come as no surprise that Moyers held degrees in both journalism and divinity. He briefly served as a Baptist minister when he was younger.

He once told me that, out of all the shows he created, the PBS documentary Amazing Grace was his favorite. It included inspirational performances of this well-known Christian hymn by musical greats such as opera diva Jessye Norman, folk icon Judy Collins, and country music superstar Johnny Cash. Moyers immerses viewers in the moving tale of its author, John Newton, a slave trader who, with extraordinary grace, turned became an abolitionist, as they share with him their own personal connections to this song of redemption.

Life s ultimate questions

This understanding of the inexpressible was evident in Moyers’ popular television series Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth, which explored life’s big questions.

I was reminded of Thomas Merton, the American poet and monk, who wrote, “Everything is emptiness and everything is compassion on beholding the immensePolonnaruwa Buddhas of Sri Lanka,” by his discussions with Campbell, a comparative mythologist, which conjured up moments that made time stand still.

I was shocked to learn that Moyers was aware of this Trappist monk. He told me that he always hoped he could have spoken with Merton, who passed away in 1968.

Sargent Shriver, the founding director of the Peace Corps, where Moyers was a founding organizer and deputy director, turns out to have introduced Moyers to Merton.

Mentored by LBJ

According to Moyers, his time in the Peace Corps was the most fulfilling period of his life. His mentor, Johnson, invited Moyers to join the White House staff after he was elected president. Johnson issued a presidential order after Moyers declined the offer.

The WunderkindAt the age of 29, Moyers oversaw the White House task forces that produced the most legislative proposals in American history when Johnson took office in 1963 following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Medicare and Medicaid, a significant immigration law, the Freedom of Information Act, the Public Broadcasting Act, and two important civil rights laws were among the programs and historic reforms created and passed during the Johnson administration.

Johnson also launched a number of groundbreaking initiatives, like Head Start, as part of his fight against poverty.

Moyers was a key figure in Johnson’s 1964 presidential campaign and one of his speechwriters. The next year, Johnson appointed Bill Moyers as his new press secretary as the Johnson administration escalated American engagement in the Vietnam War. The young man attempted to refuse once more, but the president won.

He could not serve two masters—journalists and his boss—as Moyers had feared, particularly as the administration’s Vietnam War policies grew more unpopular.

Appreciating the world around you

After leaving the Johnson administration in 1967, Moyers pursued a career in journalism. Before joining CBS News as a producer and commentator, he was the publisher of Newsday, a daily published in Long Island, New York. Tens of millions of people watched his remarks, but the network wouldn’t give his documentaries a regular time slot. He was a former PBS employee. He permanently decamped there in 1987.

Along with the Lifetime Emmy for news and documentary projects, Moyers programs received other journalism honors, including more than 30 Emmys.

Millions of Americans were able to appreciate their surroundings because to him. “Everything is connected, and if you can find that nerve that connects us to other things and other places and other ideas and television should be doing it all the time, we’d be a better democracy,” he said in 2023, in one of his final interviews with PBS journalist Judy Woodruff at the Library of Congress.

Thoughtful explanations may be overlooked in the current climate, when disinformation is spreading, professional journalists are losing their jobs in the hundreds, and some newspaper owners are stealing their editorial staff. Americans may suffer as a result.

According to Meyers, uncovering the deeper significance of people’s life requires dedication and patience. He sought to understand, for example, why so many folks in his own hometown of Marshall, Texas, have become much more suspicious resentful, even of outsiders than when he gave these folks voice in his poignant, prize-winning 1984 programMarshall, Texas; Marshall, Texas.

What can a young person who wants to follow in Bill Moyers’ footsteps—whether in journalism or public life—do in this day of escalating dangers to democracy?

Moyers said, “You can’t quit,” in response to Woodruff’s inquiry. You are unable to leave the boat! Look for a location that makes you feel like you belong, like you have a purpose, and like you can participate.

Given the current state of media and democracy, I believe it would be beneficial for everyone to heed the wisdom of this late, great American journalist.

![]()

At Manhattan University, Julie Leininger Pycior is an Emeritus Professor of History.