Written by Shannon Gibson

There were concerns that President Donald Trump’s announcement in early 2025 that the United States would withdraw from the Paris climate agreement for the second time would jeopardize international efforts to limit climate change and reduce American influence in the world.

The question of who would fill the leadership void was a major one.

Through the UN climate talks, among other sources, I research the dynamics of international environmental politics. The long-term effects of the US political upheaval on international collaboration on climate change cannot yet be completely evaluated, but there are indications that a new generation of leaders is stepping up to the plate.

World responds to another US withdrawal

In 2015, President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping jointly announced the United States’ initial commitment to the Paris Agreement. In addition to pledging financial support to assist poor nations in embracing renewable energy and adapting to climate threats, the United States at the time committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 26% to 28% below 2005 levels by 2025.

While some criticized the initial pledge as being too modest, others applauded the U.S. engagement. Since then, the United States has reduced emissions by 17.2% below 2005 levels, falling short of the target, partly due to obstacles encountered during the process.

Trump declared he was pulling the United States out of the historic Paris Agreement just two years after it was signed. He cited concerns that jobs would be lost, that meeting the goals would be expensive, and that it wouldn’t be fair because China, the world’s largest emitter at the moment, wasn’t expected to begin reducing its emissions for several years.

The decision was swiftly criticized by scientists, some politicians, and business executives who characterized it as dangerous and foolish. Some were concerned that the nearly universally ratified Paris Agreement would collapse.

However, it didn’t.

Companies in the US, including Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Tesla, have committed to achieving the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

Hawaii became the first state to ratify the pact after passing legislation. The United States Climate Alliance was established by a group of states and cities in the United States to continue their efforts to slow down climate change.

Internationally, French, German, and Italian leaders refuted Trump’s claim that the Paris Agreement could be renegotiated. Others from Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan reaffirmed their support for the global climate agreement. President Joe Biden reinstated the United States in the accord in 2020.

Other nations are stepping up now that Trump is withdrawing the United States once more and taking action to repeal American climate policies, promote fossil fuels, and impede the domestic development of alternative energy.

China and the European Union pledged in a joint statement on July 24, 2025, to reach and strengthen their climate objectives. When they stated that the big economies need to increase their efforts to combat climate change, they made reference to the United States and the current unstable and unstable global environment.

The Paris Agreement’s legal nonbinding nature, which is dependent on what each nation chooses to commit to, is in some ways one of its strengths. Its adaptability keeps it going because the removal of one member does not immediately result in penalties or make other members’ actions outdated.

As of right now, it appears that the accord will survive the second U.S. exit, just as it did the first.

Who s filling the leadership vacuum

Based on my team’s data and what I’ve observed in international climate summits, it seems that the majority of nations are making progress.

The Like-Minded Group of Developing Countries, a coalition of low- and middle-income nations that includes China, India, Bolivia, and Venezuela, is one bloc that is becoming a significant voice in negotiations. These nations, motivated by concerns about economic development, are putting pressure on the developed world to fulfill its pledges to reduce emissions and give money to developing nations.

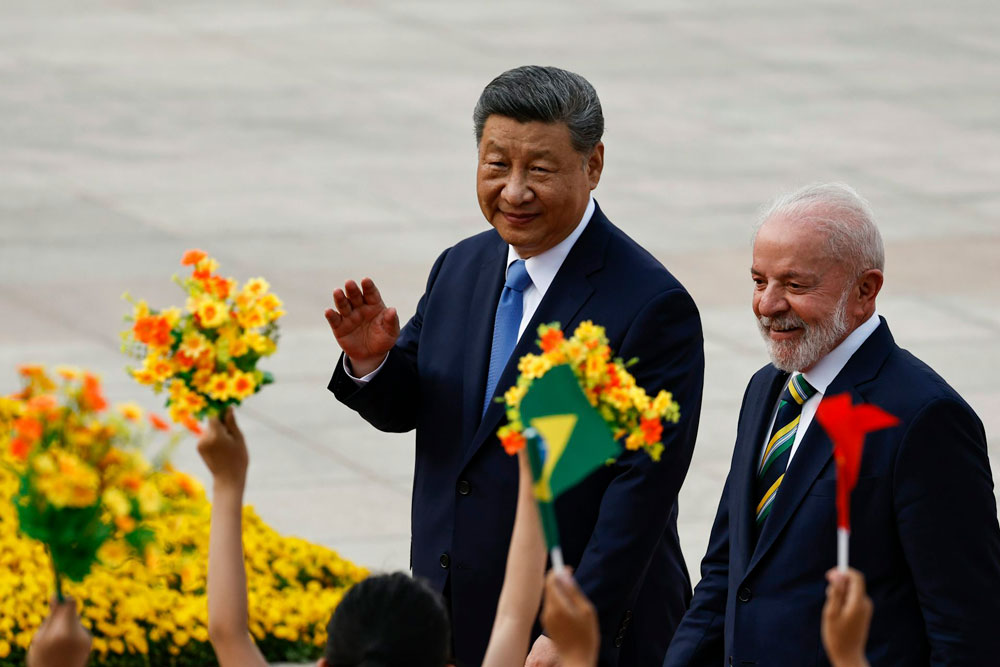

China appears to be content to fill the climate power void left by the U.S. withdrawal, driven by both political and commercial considerations.

China expressed dissatisfaction with the initial U.S. withdrawal in 2017. In addition to upholding its climate pledges, it promised to give other poor nations additional money for climate finance—US$3.1 billion as opposed to $3 billion—than the US had promised.

This time, China is taking the lead on climate change in ways that align with its larger plan to increase its economic might and influence by fostering collaboration and economic growth in poor nations. China has increased the export and development of renewable energy in other nations through its Belt and Road Initiative. For example, it has invested in wind energy development in Ethiopia and solar power in Egypt.

China has actively sought domestic investments in renewable energy, such as solar, wind, and electrification, even while it continues to be the world’s largest user of coal. China accounted for over half of the world’s developed renewable energy capacity in 2024.

China aims to peak its emissions before 2030 and then drop to net-zero emissions by 2060, even though it missed the deadline to submit its climate promise this year. It is still making significant expenditures in renewable energy for both domestic consumption and export. In contrast, the U.S. government is reducing its backing for solar and wind energy. Additionally, China has opened up its carbon market to promote emissions reductions in the steel, aluminum, and cement industries.

In an effort to become a sustainable energy giant, the British government has also increased its climate pledges. It promised in 2025 to reduce emissions by 77% from 1990 levels by 2035. With information on how particular industries, like electricity, transportation, construction, and agriculture, would reduce emissions, its new pledge is also more detailed and transparent than its previous one. Additionally, it includes more resolute pledges to finance more sustainable growth in developing nations.

In terms of corporate leadership, most American companies seem to be sticking to their green initiatives in spite of the lack of federal support and loosening regulations, even though many are keeping quiet about their initiatives to avoid inciting the Trump administration’s wrath.

About 500 significant corporations that have cut their carbon intensity—the ratio of carbon emissions to revenue—by 3% from the previous year are included in USA Today and Statista’s America’s Climate Leader List. The list has increased from roughly 400 in 2023, according to the data.

What to watch at the 2025 climate talks

The Paris Agreement will not be abandoned. The U.S. never had the authority to force the agreement into disuse because of its architecture, which allowed each nation to freely determine its own objectives.

The dilemma is whether leaders of both wealthy and developing nations can balance the two urgent demands of ecological sustainability and economic growth without sacrificing their leadership in the fight against climate change.

The COP30 U.N. climate summit in Brazil this year will reveal how nations plan to proceed and, crucially, who will set the pace.

![]()

Shannon Gibson teaches political science, international relations, and environmental studies at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts, and Sciences. This article was written by Emerson Damiano, a research assistant and recent USC environmental studies graduate.